3 Baseball Poems

•

High and Outside

I spent years heaving a baseball high and wild

into the August sky. Easy, easy my

dad cautioned me but still I threw my arm out

in a vain attempt to beat gravity and make

that baseball dangle long-limbed and light above

the monotony of Sunday afternoons

and the well intentioned whispers saying that

my time was up, that a growing girl had no

reason to feel the singular ache of a

curveball or spin impossible dreams about

major leagues and baseballs that would cheat the air

landing beyond sunflower seeds and logic

straining the hand with the promise that maybe

the next throw would spiral above all their heads

rise and rise against every law of physics

taunting the sky in an open rebellion.

—Audrey Larkin

•

Stelae

There are stelae at Palenque

that are nothing but names and numbers.

Home runs, strikeouts and stolen bases

for Hunahpú and Hunahpú

who played the sacred game back when

you had to claw for every run

not like today. The losing manager

got disembowelled on the mound

by the knife of the morning star.

I grow older, hombre, or the beardless

mozos striding to the plate grow young.

At 41 I played in Jalatlaco,

place-name meaning “sandy ballcourt.”

The Zapotec lefty decked me.

¿Cómo se dice beanball en español?

And then for once in my mortal

vagabond middle-infielder’s career

I got good wood on the pelota,

it sailed toward the sacred ring,

reached the ancient wall on one bounce.

Hunahpú and Hunahpú

played ball against the gods

in Xibalbá. They lost.

They got their heads cut off

and turned them into baseballs

and stuck them on a tree.

A girl ate them. She had babies:

Hunahpú and Hunahpú.

They finished second two years running.

They smoked the candles of the underworld,

came back to challenge in the playoffs.

They used a mosquito in center field

to steal signs. They stole them blind.

They sacrificed, they had the long ball,

they had defensive magic. They threw

the change, they threw the split-finger.

You remember the sequence from Game Six.

The Mayans carved the standings

into limestone. Learn to interpret

the statistics of heaven,

these cyclic fractals of the endless game.

—John Oliver Simon

•

Twins

Jefferson practices a big windup

from the pitcher’s mound,

Giants cap flopping over eyes

as he deals a southpaw

sidearm fastball into

my old

gray glove.

Gwydion swings an imaginary bat > at home,

momentum whirling him

laughing into a

batter’s box heap.

Jefferson continues pitching

despite the prostrate body

next to the plate

While I crouch

spearing

Jefferson’s often errant fastballs,

Gwydion crosses his hands behind > his head,

lying there gazing skyward,

“Dad, did you know

clouds are like castles?”

Ball into glove

Pitch punctuation,

“Dad, was that a strike?”

“If the wind changes their shape, > even dragons

can’t see them.”

—Jeff Brain

Aldebaran Review

Fall 2012

•

New Poems

Aaron Counts

Tobey Kaplan

Mariela Griffor

George Kalamaras

Bill Vartnaw

Laura E. Davis

Michael Daley

Linda Lancione

Crash

Many nights, as a boy, I woke to the sound of crashing.

My father, an insomniac, found solace in our unfinished

basement—a second-hand couch and a red-felted

pool table. He quieted his mind by shooting 9-ball,

something calming in the precise geometry required

to rattle a ball into a pocket with a soft thud.

Lying in my bedroom above, I could almost see

the pool balls spin across the felt and careen into

each other under the controlled force of my father’s hands.

His brother lived in that basement some months,

between jobs or wives. He slept on the worn couch,

coming upstairs to the fridge when he needed to

fetch beer or food. His laugh rasped from too many

cigarettes when he cracked jokes during the day,

but at night, drunk, the laugh often turned mean.

One night his girlfriend stood up to the bullying,

and their fight spilled upstairs, and instead of fetching

beer from the kitchen, my uncle came after a knife.

My father lay awake in his room, listening.

I squinted into the blinding bright

of the kitchen, and watched my father move

his body between the blade and a woman he didn’t know.

He gripped the thick shoulders of his only brother

and shoved hard, flinging the large man into the pantry.

The force of his collision shook soup cans loose,

and they rattled to the floor and spun towards

my uncle heaped on the linoleum. Wordless, my father

walked over and stood above his brother, paused,

then pulled him to his feet. The fight was over,

and they never spoke of it again.

On my own sleepless nights I miss my father most.

Insomniac is a lonely profession, so I haunt the shadows

of quiet rooms, looking for some life with which to commune.

I sometimes end up in my son’s bedroom, sitting on the rug

next to his bed. I wrap my fist around his and watch

his chest fill with breath. The crickets he keeps to feed his

gecko chirp, the cage clicks as one leaps a failed escape

through the plastic wall. I hold my son’s hand in the quiet,

and hope I, too can pass on what most of us only learn

the hard way: who to pull close, and who to push away.

—Aaron Counts

Another World

Before the fog lifts going up the hill

on my run home up the street

just over the curbside looks like a stick

but something makes me stop

because I saw it differently maybe a lizard a skink a gecko

with its tail cut off a few blood spots it was alive

and because I once had a leopard gecko

and often dogs chase lizards on local trails

I am trying to figure out

a lost pet or a feature of our landscape

I find a couple of candy wrappers

and carry the gecko home

put some rocks in the cracked yellow recycling bin

a hiding place a low plastic dish for water

use the worm scraps for insects

a little rug of mud leaf dry grass mulch dirt and compost

and as I’ve planned to take it the Vivarium later

so they could identify my reptile and what it needed

but I then I leave with the dogs

come home to find it

not hidden under my crude cave as it was earlier

in the sun no longer moving at all

I pull out the pitchfork find a patch of dirt I can stab

and turn over as I’m looking at it now for the first time really

gecko limbs pulled back against its body

gray green white belly design

alligatored scales diamond shaped head

eyes open to another world

—Tobey Kaplan

Exiles

Chanco had endless rows of white houses made of adobe

with thick terracotta shingles.

Old eucalyptus trees, taller than 50 feet, formed a natural barrier

between the Pacific Ocean and the village.

The people made a living producing wine and cheese.

As a child I ran through the eucalyptus forest to the ocean

in a race with my half sibling.

Small roads of red clay covered by generations of fallen leaves

made for a cushioned walk for our sandals and bare feet.

I always won all the races.

Then, on the ocean, there would be another race

to get rid of our clothes

and be the first to jump into the water.

My mother would open a basket filled with bread, hardboiled eggs,

cheese, blackberries picked by our own hands

and soda, spreading an old yellow tablecloth out on the sand.

Meanwhile Clemente would cut the watermelon he carried

from the house to the beach.

In Santiago things were different.

The day of the Coup, Mr. Monzalves visited us.

He sat on a sofa in our living room beneath a print of Picasso’s “Guernica”.

My grandfather occupied one of the loveseats.

Later I came to know that Mr. Monzalves worked for DINA

(National Department of Intelligence).

My grandfather did not talk about what Mr. Monzalves said,

but it was clear that he knew that my grandfather

was a sympathizer of Allende and that he had come to deliver a warning.

Just before I left Chile the last person I met from the Front,

in Santiago was my commander.

His real code name was Wolf.

I told him I was planning to leave the country because I could not

avoid the surveillance anymore and my good friend,

the lawyer Insunsa, had arranged for me to go to Sweden or France.

The Swedes were fond of Latin America’s cause of liberation,

he had said, and they had been receptive to Chileans

from the beginning of the Coup.

Sweden is too far, go to the South, I can’t, my family lives there,

I told him.

He wanted to schedule a last rendezvous before my leaving.

I explained that it was exhausting to get to him in my condition.

I already had my visa and a plane ticket.

Still, I finally agreed to meet, changing between different

subway lines, moving to a taxi and then to a bus to avoid being followed.

I risked everything so that Wolf could make one last effort

to get me to stay.

He never appeared. I had wanted, at least, to say goodbye.

I left for Sweden on October 24, 1985, five weeks after

my daughter’s father died.

Spring was beginning in Chile, as Winter was in Sweden.

It would prove to be the coldest winter in one hundred years

with a mean temperature of -27.2°C in Vittangi.

—Mariela Griffor

A Mother Thing

After I was settled when I got “home” from the hospital

there was a bed and a baby bed beside it, and a letter

from my mother that was forwarded from the refugee camp.

In the letter my mother said that she had missed the bus

that would have brought her from the South of Chile to the airport

to say goodbye. Somebody told her that I was leaving.

She had read about J.’s death in the newspapers. More

than 1000 people came to his funeral and the riots

that followed were covered on national TV. Reuters smuggled

pictures out of the country and in the archives of the Agency

that I would read 20 years later it would say: …the case of J’s may

turn into another scandal similar to the case concerning

the death of the three “degollados”.The last paragraph

of the letter said “I hope now when you are a mother yourself

you can understand your own mother a little bit better.”

I couldn’t answer her. Not because I didn’t have anything

to say but because it was so hard to say it. I wish I could have written

something to her at that time to bring us closer together.

But I still couldn’t think clearly. It would be a long time before I could.

—Mariela Griffor

If Not Perfect

You said nothing about the stain on the cover of Vallejo’s Trilce.

You hand me an ostrich feather as if I had never been truly alive.

We end up dying over a lunch of buttered bread.

I collide with my insides and finally get the joke.

But the table shakes as if the earth had a friend.

You and I have known one another’s toe in a different shoe.

Walk like an animal and spoon me your source.

I could investigate finishing my life by walking room to room.

The way your singular kindness covers my infatuation with all things brassiere.

The sound of midnight trains has always been erotic in their long cat-crawl and dominating sleep.

—George Kalamaras

The Vicenarian or My Twenties So Far

My therapist says, “Tell me about your twenties.” At twenty I’m born

again. Bush vote. My heart turns purple and my insides become composted

totems of faces I’d forgotten. Grandfather starts dialysis. Get homesick

in St. Lucia while eating fresh mangoes. Buy my first vibrator. Men fly

planes into buildings while women inject collagen into their lips. My hair

is short and blonde. My uncle gets Parkinson’s disease. Sleep with five people.

Turn twenty-one. Do a shot called a Red-Headed Slut. Lock my keys in the car

five times. Diagnosed with ADHD. Bush says, “Mission Accomplished”

while standing on a boat. Have sex with a woman. And with seven men.

My heart is an onion, a flaky and potent organ of flavor. Taste-tongued.

Get my first cell phone. At twenty-two I have a threesome. Reality television.

My heart thumbs it to Kansas City without me, leaving a see-through escape

route between my sternum and spinal cord. I stop praying. Forget that I love

camping. My friend Jes punches a guy in the face outside of a bar. He spits

his blood on my shirt. I tell my brother I’m queer. Mom starts getting manicures.

Turn twenty-three and have an affair with a Marine. Takes me to Washington

where he cries at the Vietnam Memorial. Date a Buddhist who drives a Honda

Civic Hybrid. Finish college and buy lots of hemp products. Get engaged.

My gynecologist tells me I have HPV. I think about dying. Get married.

Twenty-four. Heart becomes one million avocado pits skewered on BBQ sticks,

suspended in jars, the roots leaping away from the water. Get an intrauterine

device. Vote for Kerry. Get a job selling home refinances. Stop eating meat.

Gain ten pounds and decide to have an open marriage. Get a boyfriend.

And a girlfriend. I start taking Welbutrin again and find my first gray hair

which makes me smile. My grandfather has a kidney transplant. I turn

twenty-five. Hurricane Katrina. I lose my job and start temping. Ian Frazer

develops a vaccine for cervical cancer. Then twenty-six. Tell my mom

I’m getting a divorce. I get my first apartment. Buy my seventh vibrator.

Heart develops a sense of smell, scoops up grubs in the topsoil, and seeks

quick fixes of musty armpits and the undersides of garbage can lids. Decide

I’m an atheist. I pose in a pinup calendar for charity. Twenty-seven. I am

alone for the first time in six years. Heart learns how to flap prophetic,

predict the weather and spot criminals behind brick buildings. Organize

information into death or almost-death and I have my first panic attack.

I do not wear Crocs. My uncle dies. Fall in love with an Italian. Obama vote.

Twenty-eight. Michael Jackson dies. My heart is a shoe that fits both your feet,

toes curling inside like a newborn with enough space for sighing. Get my first

teaching job. H1N1 vaccine. Grandpa dies in his sleep. I dream about him

whistling. I remember I love camping. Stand inside a family of Redwood

trees and kiss the Italian. At twenty-nine listen to Ginsberg sing Father Death

I’m coming home. I learn that we are always gray with fragments of color,

not the reverse. My heart resting on the kitchen table is a machine gun.

—Laura E. Davis

first published in SPLINTER generation and reprinted by permission of the author

Kiitos, Sylvi

kiitos, the one word in Finnish I learned there

“thank you” Aunt Sylvi taught me context in 1970, Sysmå

my grandmother’s & Aunt Hilma’s sister

we did not speak each other’s languages

whenever I looked bored,

kahvi?

coffee always came with sweets

extending the familiar, (American)

she showed me “Joy” liquid

she went to the well

cranked up the heavy bucket

poured water in a big pot

on her wood stove

when the steam started rising

she applied Joy

then her dishes

it took the grease right off

clean

(like after a sauna)

of course, Veikko, her son

who lived next door

had all the modern amenities

she preferred to live as she always had

I’m learning that now

as I fail to upgrade this damned

& wondrous computer

—Bill Vartnaw © 2011

•

The Great Heart

The awkward boy,

his fingers open, sweeps hands

to brush past stray bees.

He cuts a path through wheat

beyond the other children

to keep them safe—

master of gestures—

the great heart is the taste of pears,

you’re outside, a bee,

heart that breaks its habits

when they disappoint, or

so it was in the last ice age.

—Michael Daley

The Taste of Blood

We grew up in gardens, we grew up

with hammers lying around.

At a family barbeque,

I bit you on the shoulder,

you a toddler, younger than my granddaughter.

The even teeth marks, tiny square dents

filled with red. Then the fuss.

In fourth grade, Cheryl Young slept over

and we played with your little prick.

The next day, Mom moved your bed

into the dining room. How was that,

to camp out where they carved the turkey?

No wonder when they got old

you took over the whole house.

I want to see you again, my brother,

I want to lay my hand on yours

at least once before it’s over.

But I’ll never forget that wild joy,

sinking my teeth into your tender flesh.

—Linda Lancione

Copyright © 2012 Aldebaran Review. All rights reserved.

I’ve decided to move the locus of my Web activity back to tghis blog. I’ll start by rescuing some of the terrific work I published last year in the brief virtual existence of Aldebaran Review (in print in Berkeley lo these 40 years ago and more). Enjoy!

In October, 2012, I spent a week travelling with a poetry circus, giving readings in Spanish in Rosario, San Nicolás and La Plata, Argetina, all along the shores of the mighty River Paraná. Now Lorena Wolfman and I have edited the voices of 21 poets who read those nights and caravanned those days into a special on-line issue of Aldebaran Review.

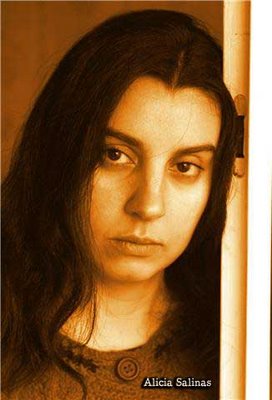

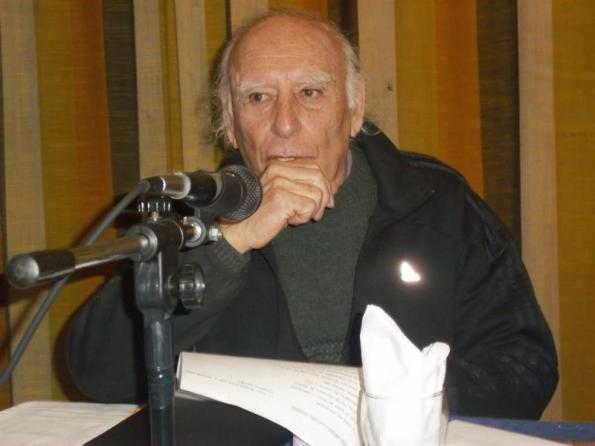

The poets range across a half-century, from Alicia Salinas (1976) ,a tough-minded glamorous Rosarina who for my money is the best young poet in Argentina, to Mario Verandi (1926), the living embodiment of San Nicolás, to the tender veterans of the Malvinas war , Martín Rabninqueo and Gustavo Casi Rosendi (both 1962), our hosts in La Plata.

This marvelous outpouring of poetry is happening out in the provinces of Argentina, which means it doesn’t count in the inevitable hierarchy of reputation closed on itself in the black hole of Buenos Aires. Read it here first.

Lorena Lobita and I translated everything into English. There arte bios and always the voice of the river. Also poems in French and Basque. I don’t think I can bring the whole site over here, but I can offer a little teaser and a link. My compilation is at <www.aldebaranreview.com>, while Lorena’a far cooler format is at <http://poetasjuntosalrio.blogspot.com/>.

Here Lorena, Pennsyklvania poet Craig Czury and I prepare to launcm helium balloons, each one affixed with one of our poems and our flag, into the skies above San Nicolás from the courtyard where Argentine independence was proclaimed. As well, rapid, seamless Stéphane Chaumet joined us from Paris, sincere Kepa Murua from Basque Country, and Juany Rojas, who danced with Lady Death, from the Atacama desert of northern Chile.

Alicia Salinas

Gallina ciega

Antes de comenzar el juego conoció el fulgor.

Pero le quitaron el brillo, las brasas. Se reveló

entonces la ajenidad de las aureolas: la luz

no es de nadie, la oscuridad

de todos.

No importa quién vendó, de dónde

la recomendación de la tiniebla.

Es hora de (vol) ver.

Esta gallina se rebela a la ceguera, al titubeo.

Otros fuegos se esparcen en la noche.

Doloroso tendal traman los pasos,

y sin embargo a su través se atisba

el final del túnel.

Hoy nadie puede la indiferencia

ante semejante voluntad

de abjurar La Sombra.

Blind Hen (Blind Man’s Bluff)

Before the game began she had known splendor.

But they took away the shine, the spark. Revealing

the otherness of radiance: the light

belongs to no one, the darkness

to us all.

It doesn’t matter who tied the blindfold, where

they got the idea of lightlessness.

It’s time (again) to see.

This hen rebels against blindness and groping.

Other fires are scattered across the night.

Footsteps weave a painful way

and yet through it all the light

is glimpsed at tunnel’s end.

These days no one can be indifferent

before such an act of will

abjuring The Shadow.

(Translation: John Oliver Simon & Lorena Wolfman)

Mario Verandi

Los hijos

De acá a 50 o 60 años

algunos cometas regresarán dócilmente

los ceibos habrán florecido otras tantas

veces en San Nicolás de los Arroyos provincia de Buenos Aires

no estarán mis huellas

de animal perplejo

indeciso frente a las rutinas menudas de la vida civil.

Para ese entonces

mis hijos también

ya serán viejos

sumidos en la contemplación de sus enfermedades iridiscentes

y la pluralidad de los mundos.

Tal vez salgan al silencio del espacio

a mirar hacia acá

hacia esta esfera doliente

donde el padre yace

a salvo del fracaso.

Children

50 or 60 years from now

some comets will return docilely

the ceibos will have flowered a number

of times in San Nicolás de los Arroyos province of Buenos Aires

there will be no trace of me

the perplexed animal

indecisive when faced with the small routines of domestic life.

By that time

my children too

will be old

lost in the contemplation of their iridescent illnesses

and the plurality of worlds.

Perhaps they will go out into the silence of space

to look over this way

towards the pained sphere

where their father lies

safe from failure.

(Translation: Lorena Wolfman)

A shoutout at Montevidayo to my translations of Uruguayan poet Eduardo Milán recently published in HOTEL LAUTREAMONT from Shearsman:

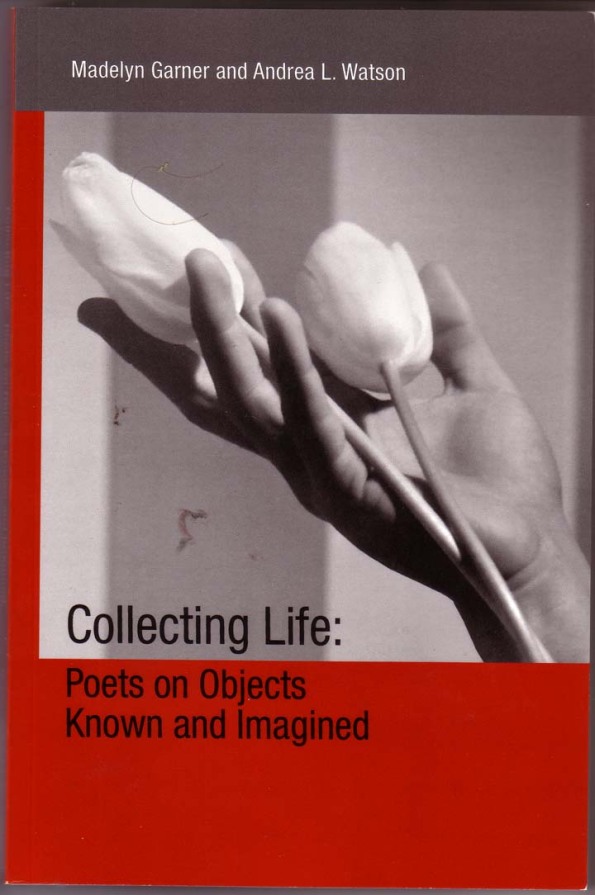

A beautiful new anthology has found its way to my door. Collecting Life: Poets on Objects Known and Imagined, edited by Madelyn Garner and Andrea L. Watson, from 3: A Taos Press : poems about hoarding, hiding, saving, buying, clutter, spiritual materialism and material of the spirit. Not a whole lot of big names among the 88 poets: Lyn Lifshin, Denise Duhamel, Gary Young, CB Follett, Jane Hirshfield, Kimiko Hahn; just a lot of really good writing.

: poems about hoarding, hiding, saving, buying, clutter, spiritual materialism and material of the spirit. Not a whole lot of big names among the 88 poets: Lyn Lifshin, Denise Duhamel, Gary Young, CB Follett, Jane Hirshfield, Kimiko Hahn; just a lot of really good writing.

My own poem included, “Isla Negra,” is about the frenetic and obsessional collecting activity of Pablo Neruda.

Here’s a mini-anthology of the six Neglected Poets I have profiled so far on this blog.

*

Edward Smith (1939-2003)

d.a. levy (1942-1968)

Donald Schenker (1930-1993)

Rebecca Parfitt (1942)

Charles Potts (1943)

George Hitchcock (1914-2010)

*

Send me your nominations for the next batch. Already in mind: Charles Foster, Joe Gastiger, Mary Norbert Körte, Jack Grapes, Morton Marcus, Flora Arnstein, Sharon Doubiago, and, because Jack said “thee and me, my friend!” Jack Foley and, naturally, myself. Send dates, bio info and poems or URL with your nominations, if you have ’em.

*

*

Edward Smith (1939-2003) was born to missionary parents in China, and

There is no image among the .jpeg's supplied to me in all good faith by Google for one of America's greatest poets, Edward Smith.

mastered Vietnamese in about five minutes when the CIA sent him in-country in ’63. Ed became fluent enough to startle the eponymous Bea of Bea’s Wok ‘n Roll in DeKalb, Illinois, with his proficiency four decades later. He was spirited out of Saigon overnight on the heels of the assassination of Ngo Dinh Diem. Ed Smith was the dominant hippie poet in 1967 Seattle in a scene that included Charlie Potts, then underwent an unfortunate conversion conjugal with whiny first wife to childhood Evangelical Christianity which cost him thirty years of poetic work that would have made his name. Smith returned to the craft around the millennium. He approached Potts and began to rev up his axe once more, drove all night to DeKalb in August 2003 to bore Rebecca Parfitt and me to tears ranting against nefarious and irrelevant Roethke while finishing her Bailey’s Irish Cream, appeared at the Walla Walla Poetry Party that fall and wowed ’em, and got the flu Xmas 2003 and died because he didn’t have health care. Ed Smith is a rapid, submarine didactic poet with great expanse and large male pattern blindness. Smith taught Potts the art of the assonant rant, or maybe they both learned it from Dorn. This is a late poem, from his comeback tour, for his older daughter.

***

Father & Daughter

*

for Lindsay

*

Divina & Heather Ferreira,

her aunt Shani Benesh

& boxes

of mostly naked Barbies

Jim Buerster’s mouth reflected

in a Matthias Grunewald picture

printed from the Internet in black & white—

Lindsay gripped it in her hand

to lay on Mrs. Kuebel

before the bells

even years after the ultrasound

showed us a girl growing

in Sindy’s tummy

###

I’m not a real man

I tell my friends sometimes

just to be funny, I don’t

golf, fish, hunt

I detest action movies

dislike fast cars,

in fact, all cars

adore quiche, salads

yellow cheese, red wine

oboes & romantic comedies

###

and yet I am a man

in the wash of a daughter’s love

frantically clinging to my arms

when the answers don’t come out right

& she cries out, “skip, skip!”

to get me to move on without an answer

evading the unpleasantness of

not knowing everything at six

###

& Lindsay, when you come some-

day to lock horns with the truth

remember the closeness of a man

who pulled you up

through fights, colds, changes

of schools, friends, your

body rounding to all

things full & sweet sixteen

for when a boy will zoom

you outa here, maybe

in a white Mustang

as in Suzy Bogguss’ “Cinderella”

your nighttime fears forgotten

in the prospects of another

young man’s toast

and yet

before you finally go

remember the man

who pushed you high

on swings

& whose curved arm

welcoming yr little

female nature to his heart

was all you knew

Edward Smith

***

***

d.a. levy (1942-1968) was understood among the poets

of the mid-to-late 60’s underground to be the most American important poet of his, and my generation. A Cleveland boy who graduated high-school entirely without distinction — his one entry in the 1960 Rhodes High School yearbook is the phrase “Hey, You!” — levy took it amiss that Cleveland didn’t have a world-class poetry scene and undertook to create one via mimeograph and coffee house. Not surprisngly, levy was busted by the Repub D.A. for reading obscene poetry to minors (the 16-year-old chick in the second row was bugged, and I do hope she’s had a happy life). Allen Ginsberg came to levy‘s aid in the grand benefit reading. levy was a telepath, a pain freak, chained to Cleveland as a Dog Warrior ties himself to a stake on the battlefield. His most important work is the North American Book of the Dead. The weight of the evidence suggests that levy sat in lotus the day after Thanksgiving and blew his brains out.

***

turn away

i have nothing to say

in all this darkness

everyone runs from

words that carry light

from the closed doors

of the mind

i have nothing to say

why don’t you just sit there

and die

a little

everyday

waiting for some naive

child carrying the

crippled bird of yr love

to say the things you are

afraid to say & perhaps

in a millennium or two

you will begin to understand

that naive child

was you

and you murdered him

in the darkness

d.a. levy

***

***

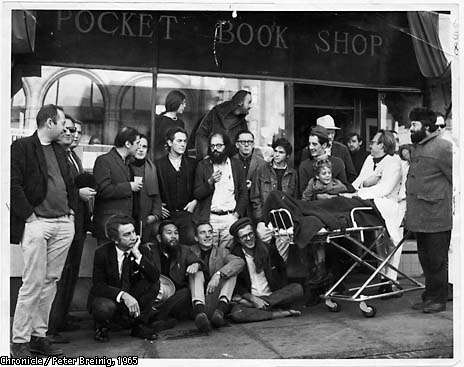

Donald Schenker (1930-1993) had a poetic career of sorts in the Bay Area, but is now forgotten except by a few deep friends. Don came out West from natal Brooklyn, married blonde artist Alice from Wisconsin, resented Ferlinghetti and Rexroth, started a successful business (the Print Mint) and practiced his chops in recurring jazzy neurotic uncommanding poems until the day in 1985 when he got the diagnosis. Don sold the business and had eight years as a great poet. He spent as much time as possible in a cabin up in Siskiyou County where he wrote all his best work — Up Here, High Time, and The Book of Owl. He got to be a grandpa before the cancer took him away. Don Schenker and I were close the last two years of his life, and I treasure that.

Claim to fame: Don Schenker's the rube standing on the far left in this iconic 1958 portrait of SF Beat poets. Shig is seated, and Lew Welch and Peter Orlofsky; among those standng are David Meltzer, Allen Ginsberg and Richard Brautigan (in the white hat).

Jorge Luján, the músico ambulante, asked me for some poetry to read at bedtime, “algo fresco, lúdico” and I gave him Schenker; Jorge’s deft translation of most of Don has had the same curious unsuccess in getting published in Argentina as Scenker has had posthumously here. Dorianne Laux, happily not a ngelected poet, will tell youhow good Don was. Schenker‘s late poems are his good as Robert Creeley’s early poems, while his early poems are as empty as Creeley’s later work. That’s bad career timing.

***

Noon at Bear Meadow

*

We were on our separate ways

to the meadow, the bear and I.

We were going to meet there.

*

He was going to stand up

and open his arms

and I was going to walk in.

*

In the middle of the meadow,

in the middle of the day,

nobody there but him and me.

We thought we’d try it.

*

But something happened.

He got there early and didn’t wait,

and I came late.

*

He was leaving as I arrived

and never looked back.

I stood and watched him go

and never called out.

*

I went back every day after that

for a long time.

Then every month, then every year.

*

In the center of the meadow at noon

I’d sink down into the grass,

close my eyes in the bright sun

and think about how close we came,

the bear and I.

Donald Schenker

***

Here’s my own elegy for Donald Schenker, written after we went out for Vietrnamese in downtown Oakland and first published inPoetry Flash.

After all I’m neglected too (“I’m Nobody! Who are you?/ Are you Nobody too?”) In her lifetime, Emily was neglected. Now she isn’t.

*

ALL OVER THE PLACE

*

—for Donald Schenker (1930-1993)

*

Don says there’s poems all over the place,

it’s practically embarrassing, and I nod

without enthusiasm, driving into downtown

Oakland thinking yeah, those two pigeons

squatting on the blue-gray sign HOTEL MORO,

how the part of it that’s a poem could fall out

between the word and the bird, or the word Moro

all the way back to the reconquest of Spain

and all the bloody hemisphere ending up

on this block I don’t care if I see again.

*

Don says he could just stop anyone

and look at them, they’re all so deep

and beautiful, and I say what’s interesting

is the stories they all carry around

stranger than fiction, stronger than truth

all these gente waiting to cross the street

each one forgetting their great-grandparents

each one forgetting to tell their children

and I’m no novelist, I can’t move a

character across the room, much less two guys

to lunch at a Vietnamese place on Webster.

*

Over bowls of translucent noodles and odd meat

Don says he always felt like the other poets

were the big boys, and I see how the grand

famous names of his peers, now pushing sixty

have turned into the padded artifacts

of their own careers, while Don’s obscurity

has kept him fresh and sweet, and Don says

he loves his tumors, the big one that hurts

in his left hip, the one that’s hammering out

among sparse hairs inside his baseball cap,

and though it’s his own death that gives him truth

I’m stuck in my heart without any words

while poems in Vietnamese are fluttering up

from all the restaurant tables around us

and escaping into so much empty light.

John Oliver Simon

*

Rebecca Parfitt (b. 1942) is my girlfriend, which raises the nepotism factor. It occurred to me there were no women on my list. Most of the best student poets, aged now about 3 – 52, I have worked with, are women. Maybe women don’t typically follow the Smith-levy-Schenker trajectory of the ambitious but truncated career. Becky‘s path is more typical of women: she never made a serious effort to establish a poetic reputation, has written a few gleaming poems in a life devoted to service to battered women, participates in a terrific writing group in DeKalb (whose dominant poet — she will hate that formulation — is Joe Gastiger), publishes occasionally, and is basically fine with that. Unfortunately, WordPress’s debvotion to the left margin won’t allow me to reproduce the elegance of how this poem, written upon seeing her first image of the being who became her granddaugher Lila, spreads pleasingly across the page.

***

After the Ultrasound

*

for my grandchild

*

All night it rained softly

all night the seals pop their shiny heads

up out of the water and look softly

at me

We lean over the boat railing

Look, seals! The children swimming!

Look!

*

I will bring you to the water

I will sing you songs of nonsense & longing

We will walk the cliffs

naming the flowers as we go

*

darling minnow

deep sea explorer

jutting knee of you

tiny throbbing heart of you

pebble knobs of spine of you

fingers fluttering toward your mouth

(just wait until you taste peaches)

pinpoint toes oh my little seal

the wonder of it!

Rebecca Parfitt

***

***

Charles Potts (b. 1943) is a force of nature. His dad was a fur trapper in Idaho; Charlie was a high-school basketball star who met Ed Dorn in Pocatello, Ed Smith in Seattle, and me and Richard Krech in Berkeley. In the apocalyptic Bay Area spring of 1968, Charlie wrote and read and promoted at white heat on caffeine, nicotine, drugs, and no sleep or food until he flipped over the line into Napa State Hospital, a painful transition he eidetically chronicled in his memoir Valga Krusa.

For many years Charlie has maintained an alternative Pacific Northwest poetry tradition through The Temple bookstore and magazine in Walla Walla, Washington. Hed rushed to the scene to be of support and assure the safety of manuscripts when Ed Smith died. There is a rock band named after him: the Charles Potts Magic Windmill Band. Charlie sometimes tours with them. Ron Silliman is one of Charlie‘s fans. It is entirely strange to me that there is an entire huge poetic universe that wouldn’t naturally name Charles Potts as one of America’s five most important poets. Go figure.

*

Fu Hexagram 24 No Hangups

*

Charlie Potts is dead

And I wonder if I should

Be opening his mail

Just as though it had

Been addressed to me

By all his friends

*

And for him as well as me

I tell you I have gone

All the way with Charlie

Back to nothing

And the cycle is complet

Ed

By the highest sound

I every heard

Going around in circ les

My name is Laffing Water

And whatever form it takes

I have plenty of

*

Changes to go through

Before I outwrite

All my errors

In longhand Legge’s English

10 year trip

With the further suggestive note

10 may be a round

Number

Signifying

*

Or

It

Long time

No see

The waiter laid on Crash

in North Vancouver

When we went in to have us

Front us a meal

Chinese English

Keeps my head up

The farthest north

I’ve been

*

Though sometimes I feel trapped

With so many other

Ugly Americans

Locked in English

Long time — no see

The blind embrace the blind

The deaf the dumb

The dead the living

Let go of me

*

I may not be one

with everything

But I am one with me

And you are 2

And we are 3

And 4 is cool

And 5 is plenty

Let’s get higher

Let’s get higher

One times nothing

Is nothing

Is me

Times it

For it is nothing

And I am it

And everything’s nothing

Belongs to you

Are part of it

Doesn’t make any difference

Whether or not I’m one

With the phone book

Dial a thought

Psycho somatic music

*

I’m completely inside

Your head now

But you can relax

For I won’t be long

And I’m not dangerous

Nor habit forming

But in case you’d dig to know

Why the sound is coming

Out of your mouth

And into your ears

Ventriloquy

Subtitled

Throwing my voice

*

You can relax completely now

I’m back in my corner

And it came with me

On the 7th day

it all returns

We got very close io it

Before it got away

But it’ll be back

The Sabbath started

With life one and is going

To last ’til dark

Today

As always

‘Cause it is

A band of invisible

4 space astral light

We find ourselves

In paradise

*

Are you ready for this

Have we been here before

But how did it end

It never ends

Mind expansion

The verb for all corrections

Think

About

The petering out of Pleistocene

The sun whips

Guided by

The magnificent completion

Of the next galactic cycle

And the final

Ice age

We passed through

With rudimentary tales

Down the Kelvin scale

Into ground

Zero

Which is the round number of

The largest perfect circle

How the genes knpw

What you all did

Greedy motherfuckers

I can be happy with nothing

Remember

Every step you take

Is in the right direction

And it’s not recorded anywhere

If everything is true

This match will sparkle

***

***

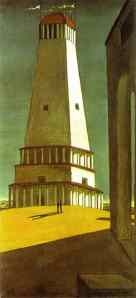

I didn’t really know the Santa Cruz Surrealist poet George Hitchcock (1914-2010) very well. Our paths crossed briefly in his active great age when I published our mutial friend the Baja California poet Raúl Antonio Cota (Hitchcock wintered in later years in La Paz). Hitchcock — a former longshoreman and labopr activist — publihed the influential and incorruptible little surrealist magazine Kayak for many years, and his famous collating parties are affectingly remembered by the late Morton Marcus. It is typical of my modus operandi that the only time I ever even submitted to Kayak was just after George had ceased publishing the ‘zine, and he returned my poems with a kind note. His was a life dedicated to poetry at the highest level, and if he had lived in New York, he woulda been John Ashbery.

*

AFTERNOON IN THE CANYON

*

The river sings in its alcoves of stone.

I cross its milky water on an old log—

beneath me waterskaters

dance in the mesh of roots.

Tatters of spume cling

to the bare twigs of willows.*

The wind goes down.

Bluejays scream in the pines.

The drunken sun enters a dark mountainside,

its hair full of butterflies.

Old men gutting trout

huddle about a smoky fire.*

I must fill my pockets with bright stones.

Syntactical language was invented 70,000 years ago by a little girl on the far southern coast of Africa.

There are several claims in the above statement that fly in the face of generations of standard linguistic hypotheses.

I have no doctorate in paleolinguistics. I’m only a poet and translator — what do you know about language? — but I keep up with the research, and in the last 44 months I’ve spent a large amount of quality time with an avid language developer, my granddaughter Tesla Rose.

Let’s start with date and place, 70K pre-present in South Africa, about both of which we can be quite precise.

69-77K back, a funny thing happened to us on our way to the internet. Geology and genetic analysis concur that our ancestral line almost went extinct.

A mega-volcano — Toba on the island of Sumatra— super-erupted, creating a ten-year nuclear winter, a thousand-year cooling trend, and arguably extincting straggling hominid bands outside of far southern Africa. Our cousins the Neanderthals, in Europe and the Middle East, and their cousins the Denisovians in Siberia, were less affected, but they, with measurable exceptions, are not ancestral to us.

The remnant bottleneck population of our ancestors, living on seafood in caves on the South African coast, minused out somewhere between 2,000 and 10,000 folks. This community was small enough for a wildfire inno0vation like syntactic language — and brain mutations to support it — to spread evenly throughout.

I draw the analogy to thermal equilibrium before the inflation phase of the Big Bang.

All present-day cultures, no matter how technologically simple or “primitive”, use complex, fluid language, with cases, tenses, moods and clauses expressing hypothesis, probability and relationship in deep and immediate past, present and future depending on who is speaking, to whom speech is addressed, and various degrees of doubt, emphasis and status. All human cultures have poetry.

Complex language, therefore, developed before current humans separated into far-flung tribes. The longest pre-globalization isolation is that of the Australian aborigines, who got to Oz around 40K and ditched their reed boats. They talk as fancy as anybody.

A recent study compares the number of phonemes used in 504 current world languages. Southern African indigenous people like the !Kung use as many as 120 different phonemes (including lots of different clicks). The farther you get from our original homeland of refuge, the more phonemes drop out (while grammar continues to weave equal complexity). English is run of the mill with 42. At the far end of the human diaspora, Hawa’iian gets by with just 13 phonemes, five consonants and eight vowels.

Prior to to our unfortunate-fortunate bottleneck at 70K, cultural change proceeds with more than glacial slowness. Over the millions and hundreds of thousands before that, hand-axes and spear-points evolve very gradually. After that point — energized by true language — we spurt headlong toward modernity in what has been characterized as the Great Leap Forward.

There was certainly a very long pre-syntactic period during which we were just beginning to use words for things. Our distant cousins the bonobo, chimpanzee and gorilla can be taught to do so. Dolphins can successfully learn elements of human syntax. True syntactic language was preceded, historically as well as ontologically, by a very long period of pidgin.

Recapitulating phylogeny, point-and-noun dominates ages one to two of human infancy. At 13 months, Tesla Rose was saying “mama,” “dada,” “ball,” “bye-bye” and “agua.” She supplemented this vocabulary with emphatic squeaks and gestures. There was rarely doubt about what she meant.

Gesture is integral to language. This is ittle discussed. ASL is a very fluid language that goes faster than talking out loud. Everyone talks with their hands, even when they’re walking down the street shouting into cell-phones. My friend Gaby and I rented a rowboat on the Lagunas de Montebello in Chiapas with an Italian girl, Hilaria. When it was her turn to row, Hilaria framed such an interesting sentence with her fingers that she dropped both oars in the lake.

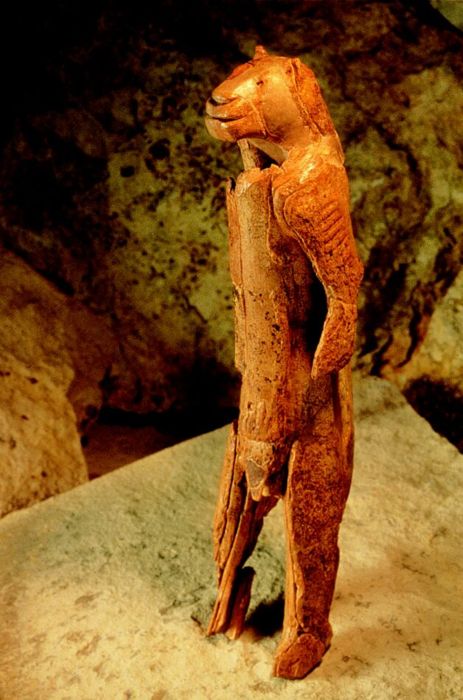

Australopithecus, homo habilis, erectus, heidelbergensis and Neanderthals represent slowly growing repertoires of distinction: colors, numbers, verbs. Probably Lucy, at 4.2M, had a few words, and used them to the point, reinforced with a lot of gesture. I suppose Neanderthals had a few hundred words. Maybe they sang. But something happened down along the coves in Southern Africa that made a dramatic difference. A system of connections evolved. If… then. When. Probably. Always. Never. I wish. Although. Because. Despite. It became possible to measure verbal scenarios against time-frames of agency and draw up contingency plans, to lie, to pray, and to make up poems.

Whodunit?

Default thought, that of adult male thinkers, has attributed the innovation of language to alpha-male hunters arguing about which flank to spear the mastodon. This scenario is offhandedly accepted and is obviously wrong.

There is no population more averse to language than adult males. Us guys are the strong, silent type, and we ain’t asking for directions. The hunt, like warfare, functions best in silence, with hand-signals. Girls are more verbal than boys, women than men; language came from the women’s side of the fire. Thus sprach Seinfeld:

*

ALLISON: (sitting) George. We need to talk.

GEORGE: What?

ALLISON: I really think we need to talk.

GEORGE: (pause) Uh-oh.

*

From the women, yes. At what age?

There is a language window in human development. Language acquisition starts at birth. By six months babies are babbling only their home-language phonemes. Before a year, they start using simple, isolated words and we’re in Neanderthal territory. At 26 months, Tesla Rose uttered her first complete sentence: I want the ball. That gets a ball faster than pointing and yelling ball! Most kids are talking fluently at three. If they don’t learn language by five or seven, viz. very rare Wolf-girl situations, they never learn it, they are permanently cognitively crippled. Syntactic language was invented in the childhood window.

I say “a girl” but it had to be a cohort of girls, chattering, gossipping, making up their own secret code, turning pidgin into creole. Tt was Greek to the guys, and the grownups had no idea what they were talking about. In the next generation, syntactical mammas talked to their kids, including boys. Syntactical girls wanted to mate with guys who could talk to them. The new fad, the new slang, would have spread through the small human community is very few generations.

Shortly after the 70K bottleneck, humanity leapt from our southern African refuge with lightning speed. By 60K we were in Israel and the neighborhood, where we interbed minimally with Neanderthals while otherwise consigning our beetle-browed cousins to the dustbin of history.

African people have no Neanderthal DNA; everybody else has something on the order of 3-6%. Thanks to slaveowners’ droit du seigneur (think Tom Jefferson and Sally Hemings) and Native Americans’ lack of racism, African-Americans have a lot of ancestry from “everybody else” and so largely share the Neanderthal connection. Melanesians and some folks headed for south India interbred with Denisovians in Southeast Asia. The DNA we took on from our pidgin-speaking relatives seems particularly to strengthen our immune system.

Africa, source of multiple waves of human origin, is more diverse than the rest of the world combined. Nor is it any coincidence that 17 of 20 world records in men’s running, from 100 meters to marathon, are held by African descendants.

By 40K syntactical humans got to Australia and were ethnically cleansing Neanderthals from Europe. The last Neanderthals made their final stand at Gibraltar about 30K. Behind the front, Aurignacian shamans were painting marvellous wildlife scenes in caves. Maybe as early as 30K by boat, and certainly in a massive megafauna hunting party around 11K, humans poured into North and South America.

With global warming after the Younger Dryas, women in five continents started cultivating wheat, barley, rice, corn, beans, and potatoes, making cities, kingdoms, laws, politics, and religion possible. Written language was invented about 6K to deal with transport and exchange of agricultural products. The rest is history.

Language keeps changing. Kids are always inventing slang. The first recorded use of the verb “to google” dates from 1998, but the adjective “cool” goes back to African roots.

Language evolves at a constant rate, separate populations achieving mutual unintelligibility about a thousand years out; language families can be dated like carbon-14. We know the Romance languages separated from Latin, and each other, about 2K. Proto-Indo-European has a well-established vocabulary going back to about 6K (and was probably spread by the whirlwind movement, out of Central Asian steppe, of the first folks to effectively domesticate horses).

That’s less than 10% of the way to the origin of syntactic language; attempts to trace the putative tree farther back are not convincing. Proto-Nostratic, at 10-12K, has been elaborated as a hypothetical ancestor of Indo-European, Semitic and Dravidian, but there’a a lot of noise in the data. A word list for Proto-Human includes who?, what?, finger and vagina, but the suggestion for “water” is akwa, which sounds like special pleading. The rising intonation at the end of a question seems to be universal and was probably present from the beginning.

Language is the central human invention, the hive which we are ceselessly elaboratng, even as I speak. Language sprouts meta-languages, of which music and mathematics are the most salient examples. Cyberspace, where you are reading this, is based on AI languages and includes acronyms and emoticons. LOL. If we wetware people are supplanted by cyborgs at the Singularity, I expect the language enterprise to continue and accelerate.

I suspect humanity will not speciate again until another bottleneck reduces us to a fused community. Speciation is extremely likely to occur in the isolate population of a colony on Mars or Enceladus or Tau Ceti. That is, if we ever manage to stir our ass from the muddy ground of self-induced economic dysfunction and fling ourselves back into space.

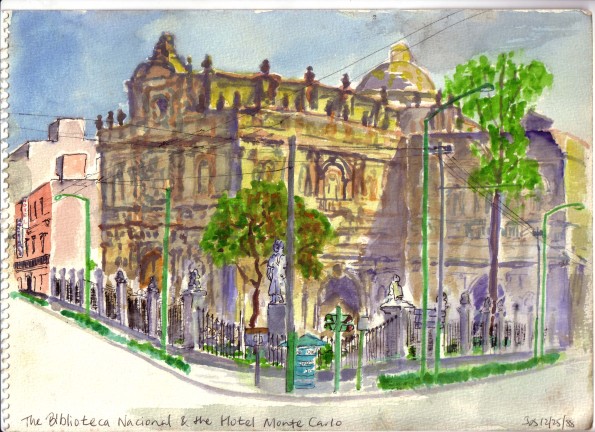

Esquina República de Uruguay e Isabel la Católica. Foreground: the former Augustinian convent and Biblioteca Nacional, and statue of Alexander von Humboldt, who slept on this block in 1806; background, the Hotel Monte Carlo.

I fell in love with the Spanish language when I was forty years old.

I took French for six years in high school and college and hated it. Jeanne Case, my French teacher at the Putney School, used to tell me, “Jean, you arre ‘aving mecca-nickel di-fickle-tees.” I memorized endless lists of verb tenses concerning unlikley situations in the past or future (this is stupid!) and with exception of Villon, Rimbaud and Appollinaire I hated the French poets.

Finally, at twenty-four, after I backpacked around Europe and the Middle East for six months, and my gender mistakes (C’est la change, monsieur, c’est feminin) sufficed the French to affect total incomprehension, I decided I was bad at languages. Plus ça change.

I got interested in Spanish around 1980 out of some geopolitical notion of continental solidarity. The Sandinistas had triumphed in Nicaragua, poets were coming back from there with glowing faces talking of workshops, the talleres, that were just like California Poets In The Schools but with adults, most of them recently illiterate. Meanwhile the Republicans were beginning to sponsor the Contra terrorists.

For years I had styled myself a poet of place in California, a watershed poet, writing about lichen and coyote-scat, following in the bootprints of John Muir, Gary Snyder and my mountain-climbing grandfather Oliver Kehrlein.

The terrain I was stomping made it increasingly obvious that the Spanishlanguage haunted the political meaning of earth not too far below the Anglo surface of North America.

Sure, the California Indians lived here first, Olema, Petaluma. I already had written more than my share of feather in my snakeskin headband, bearshit in gleaming in the trail poems. Spanish was scattered in names like desert varnish along my highways: Anza-Borrego, Aguas Calientes, Los Angeles, Ventura, San Joaquín, San Rafael, Corte Madera, Santa Rosa.

And this next part feels artistically embarrassing to admit, but I was plotting a science-fiction novel set both in Mexico and an alternate California in a timestream wherein Hernán Cortés took an arrow in the eye on his way out of Tenochtitlán on the Noche Triste and the Americas were never conquered by Europe. I had some good California scenes; San Francisco is Puerto Buenu, a tough harbor town with Ohlone suburbs. I figured I ought to do some research at the scene of the crime.

Later I spent a couple of years taking that meshugganah novel through interminable drafts, increasingly encrusted with local color, language and grudges to settle. All my women characters were smoking cigarillos: mirages of sexual triggers. I tangled myself impossibly in paradoxical time-travel intrigues. A few people bravely read it and liked it. But after all it seems I am not a novelist. I still want to write it just one more time. Sigh.

So I self-studied for a few months out of a book by Charles Berlitz (later spent two full years in the Vista College classroom of the incomparable maestra Carlota Babilón) and flew to Mexico City for the first time in April 1982. I got a room in the Hotel Monte Carlo a couple of blocks from the Zócalo on the Calle República de Uruguay because D.H. Lawrence stayed there in 1924 when he was thinking about writing The Feathered Serpent. That same afternoon I headed out to the Museo Nacional. Here’s my first jetlag-stunned uncomprehending ride on the Metro, emerging into the teeming daylight of Chapultepec:

*

more than I can take in

crush of people

train windows open

rushing through darkness

sweet little girl

clutching her blind mother’s hand

pyramids of chewing-gum

cunningly arranged

Indian woman in blue rebozo

taps rhythmically with a peso

on black iron railing

my Spanish withers

***

Rhapsodic were my inscriptions wandering in through the monumental, comprehensive Museo Nacional de Antropología. Paleoindian, Olmec, Teotihuacán, Toltec, Aztec, Maya, Nayarit and Sonora masks and gods and weapons and trade goods…

*

I can’t sing

my tongue is stone

hombre

limbs bound like reeds of years

snake’s coils disappearing,

spiralled down

*

Mictantecuhtli stole a bone

and then she couldn’t find it

*

That first night in the Monte Carlo I dreamed that I had better cease and desist writing poems to my third ex-wife and tacking them up on the doors of my father’s modest Connecticut summer cottage, because it’s making my girlfriend, or whoever I’m supposed to be in love with, nervous…

Later I lived entire summers in the Monte Carlo. One summer I managed not to speak any English for about six weeks until interviewed about my California Poets In The Schools projects by a reporter from the English-language Mexico City News. After ninety minutes of English my jaw ached…

Years after that I stood in front of the Stone of the Sun to teach a poetry lesson to Mexico City sixth-graders about their experience in the 1985 earthquake, in which maybe 55,000 people died (who’s counting?) and a tumbling shoddily-built parking garage fell and dealt a codazo to the Monte Carlo, once a convent attached to the Augustinian church on the corner, and braced on colonial foundations, remained standing and opened for business again after a year of renovations. I got to peek upstairs at my old room cracked and shaken.

Lonely and desolate in the morning I found my way to the blue-tiled Cafe Tacuba, situated about where Cortés had or had not taken that alternate arrow in the eye. Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz (1648-1696), the greatest Spanish-language poet of her half-century, gazed amiably down as I devoured arroz con dos huevos for 55 pesos. My depression had gone away.

Later, my steady breakfast cafe in the Centro Histórico was the Esla on Bolívar. Mario Ramírez, waiter, friend and teacher, would shout ¡Avena! to the kitchen when he glimpsed me stumbling toward the door and greet me across the formica counter with two copper samovars, one of potent thick coffee, one of steamed milk. “Estamos envenenado al planeta,” Mario confided. “We are posioning the planet.”

Porque la vida no vale nada, wailed a blind singer by the black cathedral fence. Years later, Becky and I stood in there off the Zócalo as the moon, Coyallxauhqui, eclipsed the sun, Tonatiuh. Night fell at noon and Venus glowed around the ghostly coronaat the head of a sequity of stars as patrol-k;lights spun blue and red and the crowd chanted ¡México, México! as if the astronomical portent were a soccer game in the Copa Mundial.

I made my way through sidestreets to a local bus for Tenochtitlán and the pyramids of Moon and Sun 1500 years old. Tramping the ruins, I felt oddly disconnected, probably mostly jet-lag:

*

all this is a surface

clay flutes muy baratos

dry season

I am not close to the heart of the pattern

*

At close of day, with heavy heart, I stood awaiting a bus to return to the megalopolis. One arrived, I swung aboard, but when I offered to pay everybody laughed with comments far too fast and fluid to catch. They took my money anyway and swung down at a corner, returning with armfuls of six-packs. It was the arqueólogos returning from a day of digging for simple implements representing people’s everyday lives in the middle-class barrios below the imposing pirámides of Teotihuacan.

We began to converse in a lively way over cracked-open cervezas, me fearless in then-execrable Spanish, using the present tense for all possibilities. When we got to the Centro the archeaologists invited me out for cena and más cervezas in the Bar Gallo.

The first Spanish joke I ever got (though it probably had to be explained to me) was when I showed them a photo of my then 13-year-old daughter, and Sergio cried out “¡Suegro!” (father-in-law)

There was a certain anti-Americanism in their politics, which I basically agreed with, the current malignant Alzheimer’s Republican president not being exactly, as I would later learn to say, un santo de mi devoción, and the upshot of our cena was that Sergio and Chucho invited me to return with them that very night to Tenochtitlan.

Why not? ¿Por qué no? From the Gallo in el centro we three hurried by Sergio’s parents’ apartment in Los Doctores where our pace slowed for polite and leisurely tasas of chocolate a la olla, then sprinted to the Monte Carlo where I gathered my things, thence at midnight por el Metro out the northern line to Indios Verdes, Green Indians, where we barely caught the very last bus for Tenochtitlan, squeezing painfully aboard. I’ve been packed that closely in since on the Metro or in second-class buses in Guatemala, but in my middle-class gringo existence this was the first time my personal space had been so absolutely stripped away, and I understood that if I died right then I would remain pressed upright by my neighbors.

In Sergio and Chucho’s dorm room we sampled some tasty local harvest of the benevolent herb. Then we wandered out in ancient darkness into the city once the most populous, powerful and beautiful in the Americas.

I had hurried past the feathered serpent stairway already in the ashen light of noon, surrounded by tourists from Japan and Pensecola. Now, at 3 am, we three mosqueteros ducked under the ribbons holding back the phantom erstwhile daytime crowds. The mouths of the plumed dragons were black cenotes of darkness. “Si te metes el brazo y dices una menteria, te lo va a comer,” Sergio told me. Whatever inanity I whispered must have been some kind of truth.

We clambered up the forbidden stairway between the bird-dragon heads of Quetzalcóatl into starry night. Sitting there under the overarching clouds of the galaxy, we talked largely, if rather brokenly on my part, about poetry and destiny. Stars fell from the sky. “Estrella errante,” whispered Sergio.

Over the ensuing three decades, my Spanish got a lot better (though there’s always an annoying remnant of that horse-muscled-jaw gringo accent). I’ve travelled largely throughout Latin America. My longest voyage 1995-96 nine months from Mexico to Chile and Argentina culminated in my participation in the Festival Internacioonal de Poesía in Medellín, Colombia and was chronicled in 131 eight-line stanzas in Caminante, which Gary Snyder blurbed “a major poem.”

I’ve published many hundreds of poem-translations from Spanish to English and poets have translated me. Sergio Gómez became perhaps the most respected Mexican archaeologist. Chucho Sánchez became a well-known adviser to Subcomandante Marcos and spokeman for the EZLN, the Zapatistas. Chucho showed up at my book party in San Cristóbal de Las Casas for Son Caminos, my poems translated into Spanish by many of the best poets in Mexico.

,

That night in Apri 1982 is when I set my foot on the Latin American version of the path, which as Antonio Machado tells us, is made by walking:

*

Caminante, son tus huellas

el camino y nada más;

Caminante, no hay camino,

se hace camino al andar.

Al andar se hace el camino,

y al volver la vista atrás

se ve la senda que nunca

se ha de volver a pisar.

Caminante, no hay camino

sino estelas en la mar.

My notes on a reading by the late great Santa Cruz poet George Hitchcock (1914-2010), on October 5, 1980.

Intensive detective work in my 28th blue notebook does not reveal the venue of the reading, only that I paid a 75-cent toll on that date to cross a bridge. San Francisco, probably. Somebody named Ivan, probably Argüelles, was the M.C. Evidentally it was in a bookstore-cafe. Could it have been the Blue Unicorn?

The first link takes you to a deeply-felt essay by Morton Marcus, who knew Hitchcock for decades and was frequently published in his seminal magazine kayak. Marcus never missed a kayak collating party. I never went.

Marcus narrates Hitchcock’s labor-organizing background in the thirties, when he wrote a sports column signed Lefty for the People’s World. He was famous for a 1957 colloquoy with the counsel for the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), who got Hitchcock to admit he did underground work. “Of course I do! I’m a gardener!”

Hitchcock was a protegé of Kenneth Rexroth, and kayak published early work by current U.S. Poet Laureate Philip Levine, Charles Simic and Raymond Carver, among others. George and I collaborated a little bit years later; George spent every winter in La Paz, Baja California, where he became good friends with the poet Raúl Antonio Cota, whom I translated.

The Blue Unicorn reading:

[GH’s] first poem [refers to] Conrad Aiken, De Chirico, Black Diamond Bay. Antique clarity with psychological focus. GH sitting in a wicker chair, wearing a white Panama hat, smoking a [Cuban] cigar. Voice shoots out of space with authority. Sharp mixture of vivid and reduced, contexted and not.

*

Each April another government

evaporates at the Finland Station.

*

Unavoidably. The fact is. A little too Mozartean in the quilt poem. Insects restore Italian focus. Detail. Imagistic conviction reminds me of [L.A. standup poet] Jack Grapes, from quite another tradition.

His poems fall into pentameter, catch themselves, painterly. His dedication: attitude weakens “roseate wound” O god.

*

Sleep settles its lion

on top of a distant red tower.

*

Meanwhile, as the reading proceeded, two young Black men went into the attached cafe, robbed the register without a weapon, passed quietly through the rear of the crowd, applauded as Hitchcock finished a poem, and slipped out into the night. A flawless poem of its kind.

I’ll leave you with a George Hitchcock poem that I wish I wrote:

*

AFTERNOON IN THE CANYON

*

The river sings in its alcoves of stone.

I cross its milky water on an old log—

beneath me waterskaters

dance in the mesh of roots.

Tatters of spume cling

to the bare twigs of willows.*

The wind goes down.

Bluejays scream in the pines.

The drunken sun enters a dark mountainside,

its hair full of butterflies.

Old men gutting trout

huddle about a smokey fire.*

I must fill my pockets with bright stones.

One of my more pleasant duties in my three years (1978-81) of herding cats as Statewide Coordinator of California Poets In The Schools was to attend the NCTE (National Council of Teachers of English) regional conference at Asilomar, on the Pacific shore near Monterey, California, and schmooze with the assembled potential clients seeking niches for poets in classrooms. The Asilomar NCTE’s had a truly distinguished set of presenters. My final year the keynote speaker was the renowned American mythologist Joseph Campbell, author of The Hero with a Thousand Faces. Here are my notes (necessarily framentary, explicated only when possible) on the truly unique take on Homer that Joseph Campbell presented at Asilomar on September 28, 1980. Any flat inaccuracies are undoubtedly mine rather than Campbell’s.

One of my more pleasant duties in my three years (1978-81) of herding cats as Statewide Coordinator of California Poets In The Schools was to attend the NCTE (National Council of Teachers of English) regional conference at Asilomar, on the Pacific shore near Monterey, California, and schmooze with the assembled potential clients seeking niches for poets in classrooms. The Asilomar NCTE’s had a truly distinguished set of presenters. My final year the keynote speaker was the renowned American mythologist Joseph Campbell, author of The Hero with a Thousand Faces. Here are my notes (necessarily framentary, explicated only when possible) on the truly unique take on Homer that Joseph Campbell presented at Asilomar on September 28, 1980. Any flat inaccuracies are undoubtedly mine rather than Campbell’s.

*

The function of religious institutions is to defend yourself against an experience of God.

Odysseus spent twenty years in passage through a violent male world where woman was booty. To return from that experience, to reach home again, he had to pass through a debriefing which included threats and teachers. The threats were monsters: Cyclops, the Laestrygonians. The teachers were nymphs representing three-fold aspects of the Great Goddess: Circe (Aphrodite), Kallypso (Hera) and Nausicaa (Athene). These three ladies were supposedly judged by Paris: a male put-down of the feminine.

The Old Goddess was animal as well as human. Pig, deer and water (in the Odyssey) are the powers of life. When she becomes human, the animal is her associate. Eating and drinking, we partake of the universe. The goal of all living is become transparent to the transcendent. The radiance of the transcendent permeates the world of time-space. Squirrel or saint on the shores of experience.

The function of art, of the poet, is to make things ONE, as opposed to war, this against that: DIVISION. That is the large movement that works in Homer. Male and female versions at work and at loggerheads in the text.

Aphrodite, born on the half-shell, out of the ocean, was the cause of the whole thing. Gaea was born inside the father-womb of Uranus. Uranus was so tight, so uptight, that his children couldn’t get out. Chronos was the eldest child, took a sickle and casbtrated his father, throwing his genitals into the sea. Aphrodite was born from thence: this version is another male put-down.

The Goddess was there first! She is time and space and logic. We are bound in those realms, and she is the binding circle. She is being and act, woman and man, love and war together, the ground of being, always naked. There is a bird in her hair: the Holy Ghost. And a snake too. They are the messengers of Aphrodite. The bird is released spirit, the snake bound to earth. The serpent of the moon shed its skin to be born again. Significance of the snake reversed in Judeo-Christian tradition.

Aphrodite as the mother, the fingers of a baby on her nipple: Eros. Her other male associate is Hermes, with wings in his hair, wearing a white suit at the gate of death, he opens the way. Hermes the dog and the three goddesses. Hermes is Mithra, with a stocking cap. The sun. Christmas is Mithra’s birthday.

Paris is a lounge lizard, an Indo-European latecomer. Accosted by Hermes, he sets up an Atlantic City beauty contest between the goddesses with their three circles of destiny. Another inflexion: the three Eumenides. Hermes tells you: gotta face ’em. Hermes makes you make up your mind.

In the male tradition, Aphrodite offers Helen as a bribe to Paris. Paris abducts Helen. Menelaus objects: “Helen in my property.” Achilles and Patroclus are draftees. Odysseus, newly married, tries to act crazy for the draft board, hitching incongruous animals to his plow. Agamennon is a tough shrink: he sets Telemachus in the furrow. Odysseus flinches from plowing under his own and only son. “You must be sane,” concludes Agamennon. Catch-22.

There’s no wind for the fleet, so the male priest Calchis declares they must sacrifice Iphigenia. Clytemnestra sees her daughter taken away, with nefarious consequences. Clytemnestra has had bad press. In the female tradition, Artemis recues Iphigenia. Homer didn’t know this.

The Iliad among the Dorians is contemporary with Judges and Joshua among the Hebrews. Jephthah also sacrifices his daughter Iphis. We have both traditions. That’s why we’re in such a mess.

Achilles and Agamemnon in a spat over Briseydis: who gets the blonde? Achilles sulks in his tent. Soldiers in their free time, playing chess. Come on, come on!, coax his friends. And the Iliad begins: I sing the wrath… Patroklus killed, Achilles goes to war for personal revenge, a bad reason if you want to keep your soul clean.

Unlike the Old Testament, there are personal heroes on both sides. Achilles is a sports hero: Joe Namath. Hektor is a real human being. Hektor will be no match for Achilles. Andromache knows it and tells him not to go. Parallel here to Arjuna and Krishna. Astyanax, their son, “little star,” is afraid of his father’s helmet: bad omen for the male side. Achilles drags Hektor three times around the walls of Troy to his death, a magical act, unwinding the walls’ magic. Athene suggests the strategem of the Trojan Horse. The classical tradition survives and is transformed in Europe: the God become heroes. Virgil with Aeneas. Arthur.

Christianity is more Greek than Hebrew. The swan descends to Leda, the dove to Mary.

Helen, taken back by Menelaus, ends up in Egypt. Agamemnon is killed by Clytemnestra, Clytemnestra by Orestes. Is he his mother’s or his father’s son? Two mythologies clash.

Apollo purifies Orestes by pig sacrifice: domestic cult. Tusks of the pig: two crescent moons, blackface between. The blood of the pig puts the Eumenides to sleep. Circe’s animal is the pig. Odysseus meets his son Telemachus in the swineherd’s shelter.

Sword in hand, Odysseus, a wary crazy Vietnam vet, sails his twelve ships first north to Ismarius, where they sack the town, rape and pillage. Boreas, the North Wind, then blows him south to Africa, to the land of the Lotus Eaters. The magical experience, LSD, the shore of dreams. California.

Odysseus goes ashore on the Isle of the Cyclops with the solar number of twelve men. Entering the cave, the narrow gate, he confronts Polyphemus the one-eyed, a reduced negative form of power facing within. Asked who are you? he responds “No man,” divesting himself of secular fame as he enters the underworld.

Polyphemus eats six men, three sheep, nine in total, a goddess number. The sharpened beam that blinds him is a convenience from the magical realm described in gory detail. When he cries out and tells his friends No man is killing him, they tell him: “keep it to yourself.”

The central problem in the Odyssey is how to coordinate the adventures of the solar hero and the woman who weaves the world. Odysseus is the Ram, the Sun-God, on his way to the Island of the Sun, to which he is introduced by Circe. Penelope weaves and unweaves like the moon. The lunar and solar calendars mesh in a twenty-year cycle. The moon is life throwing off death, bound to the wheel of the world, reincarnation. The sun casts no shadow, the radiant sign of life disengaged from time, nirvana. Locate the eternal light. Am I consciousness or body? You don’t have to quit life to get to the sun. The full moon, the mid-point in man’s life, the 35th year, Yeats, A Vision, Dante.

Aeolus of the winds, Stromboli, the newspaper office in Joyce’s Ulysses, spirit that has left earthly character behind: the danger of inflation, puff yourself up. The temptation of Jesus, to turn bread into stone, to convert spiritual kingdoms into economics and politics. Alternatively, cast yourself down. Given a wallet full of winds, Odysseus falls asleep, his men open the packet. “We blew it.”

Ugly adventure among the Laestrygonians, manic depression, cannibalism the ultimate depressant. We are all flesh, and that’s all. Throw rocks at them, they sink eleven of twelve shiops, more divestiture.

Circe of the Braided Locks, weaving appearance, weaving Maya. Odysseus, you’re in trouble now: a woman whom you can’t push around. Male brute force against woman’s magic arrow. The Iliad is ruled by Zeus and Apollo, the Odyssey by Hermes.

Odysseus undergoes two initiations: that of the Underworld and that of the Lord of Light, Circe’s father. The underworld is the ancestral world where all bodies are the shadows of spirits.

Tiresias saw two serpents copulating, stuck his staff between them and it made a woman. Zeus and Hera, arguing about who enjoys sex more, man or woman, ask Tiresias, who knows both, and he answers “woman, of course.” Hera took this badly and struck him blind. Angry because she could no longer say, “I’m only doing this for you, dear.”

The power of prophency, the inward eye. Odysseus realizes male and female are one being, one androgyne. Next, please. Circe predicts obstacles. Scylla and Charibdis, the fine craft of bondage.

The Island of the Sun, taboo against killing the oxen: a warning against spiritual materialism. Odysseus again distracted, falls asleep, his men eat the oxen, followed by complete shipwreck disaster, only Odysseus is left. Ishmael after the wreck of the Pequod.

Odysseus fails to pass the sundoor, he is thrown willy-nilly toward Penelope again via Kallypso. The function of women in relation to the Hero: knock him down and put him together again. This is not the Hindu transcendence of the world, but living in the world with knowledge of the light.

Seven years have passed, says Hermes, it’s time. Odysseus is washed ashore in the land of the Phaecians. Nausicaa, the third goddess, is doing laundry, and tossing a ball (goddess roundness activity). She alone has the courage to confvront the phenomenon of a naked gentleman. In her role as Athene, Nausicaa brings him home to Daddy. “Wal, stranger, where ya been?” “I’m Odysseus.” He returns through the threshold, regains his secular identity.

Another mysterious passage: Odysseus falls asleep on shipboard, is left asleep on the shore of Ithaka.

Telemachus is the young man of 21 (three times seven, goddess numbers). Athene tells him : Go find your father. First he visits with Nestor, the old football coach. Then son and father meet in the swinehard shelter in Arcadia. Odysseus arrives as the Tramp. “Don’t mention my name.” Old Nurse is the first to recognize him by the scar on his though from the boar’s crescent goddess horns. Adonis was slain by a boar. Buddha died from eating pork. And the Old Dog.

Bending the bow through the twelve signs. Odysseus is the sun; the suitors, the stars. Final reconciliation with Penelope. Leaving the bearded blind Poet on the shores of experience.